Notes from the editor

Gravity

Not surprisingly, the first impressions of people's visit to the forests of Kalakadu and Mundanthurai are diverse. Each personal account in this issue of Agasthya not only talks of their first time experiences but also how their opinion has since changed. The one common thread in all the articles is the strange pull that all the authors felt towards the forest of KMTR. For some like Thalavai Pandian, the pull has been a life changing experience putting them on course in their careers. For others, the pull ultimately had a 'push' effect opening up windows for a better understanding of how different things function. From things learnt in KMTR, researchers are now expanding on a national scale and I am certain that the combined magnetic effect will one day pay dividends for conservation on a large scale.

- Allwin Jesudasan

A view of KMTR through Aruvithalai

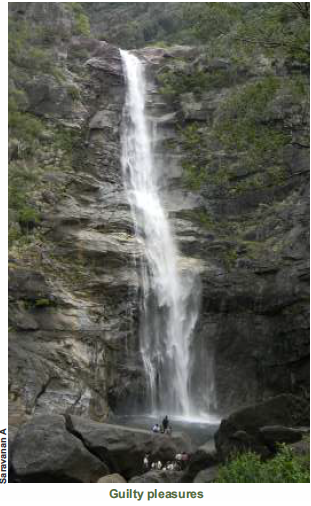

Singampatti, my native village, is a stone's throw away from KMTR. Even today the hills abutting village are referred to as Singampatti hills by the Forest Department, researchers and people. Some plants too are named after Singampatti(eg Phyllanthus singampattiana) perhaps because they are found only in these hills. From my childhood days, I enjoyed bathing in the water flowing in the Manimutharu river, picking up pulichi fruits all along the edges of forests and collecting drift wood washed into the Manimutharu dam. When I got a little older I made forays with my friends to Manimutharu water falls to have a bath. Though I enjoyed all these that emanated from KMTR, somehow I was not particularly struck or impressed by it yet.

I realized I was already 20 when I got my first chance to trek inside KMTR. I remember it very distinctly because it was in that year that there was a severe water crisis all over the district due to an impending monsoon failure. It was then that I had accompanied people from my village to Aruvithalai, a water-fall, where a special pooja was organized, as per the old hallowed customs, urging the nature and the gods to rain down on our village. For the first time, I saw the many big trees of the forest. I also saw the green forests all along the river Thalaiyanai. The water was so clear that one could throw a gold ring in the water with enough confidence to be able to easily retrieve it back in a minute. We ate the food that we had packed and took a dip in the Thalaiyanai. Later we walked for about three and a half hours and reached the Aruvithalai. It was strange that as soon as we reached Aruvithalai, it started to drizzle. Water was falling from more than 30 feet above and the pool must have been about 80-100 feet wide. Locally, we called such pools as 'Kasam'. I had never seen a waterfall so wide and a Kasam so big. It was a magical moment. Ironically, I missed the pooja for which I had made the trip. The waterfall and the surrounding forest drew all my attention. It was such an amazing experience for me that I secretly wished for the monsoon to fail every year so that I get an opportunity to visit Aruvithalai. After the pooja we camped for the night in the forest, a first for me, and while lying down, I gazed at the moon and stars before I drifted off to sleep. Next morning we were served rice with mutton curry for our brunch and somehow this mundane combo felt tastier in the forest. Soon we were on our way back. For the next one month, whenever my peers met we only spoke about the experience of that trek and the beauty of forest. It was only after 8 years that I got to re-visit Aruvithalai. But then I missed all my friends who have drifted apart, working in various cities, some across the state, a few across the country while another few across the world.

-Mathivanan

mathi@atree.org

Gain some, lose some

A paradise flycatcher male swooshed above our heads as its tail made elegant white waves in the wind. And I said to myself: welcome to paradise. An incredible bird to see anytime, let alone on your maiden trip to one of most fetching and captivating forests of India. The month of January was a time when the teak monoculture and the dry forests of the foot hills were in fresh green flush after the retreating northeast monsoons. So when I first saw the Manimutharu falls, it seemed like an expansive milky cascade flowing from the deep arcane womb of the Sahyadris. You may blame the hackneyed analogy on the early enthusiasm and romanticism of a neophyte, not yet affected by the disillusionment and despondence that the field of conservation later offered in great abundance. Near the falls was a temple around which scores of bonnet macaques frolicked, while carefully avoiding the fat, wet, semi-naked men coming out to pray after having the mandatory 'falls' bath. Offering my own two bits of prayer at the temple, I thanked my beginner's luck and prepared for the long ride ahead.

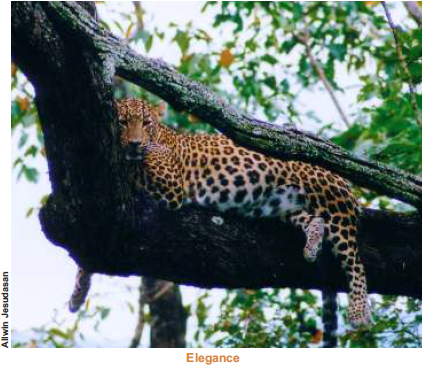

And then I saw a young leopard, for full ten minutes, with just air and metalled road between us. The leopard was stalking a Nilgirilangur and was definitely doing a bad job of it because the langur was clearly alarmed and it constantly teased the leopard from the safety of the tree canopy. I was about to turn and run back away from the hungry predator but Vivek, the experienced among us, felt that standing still and letting the leopard have the right of way was a better idea. Deciding to back experience over instinct, I waited for the leopard, who gave up after 10 mins as it elegantly ambled down the steep and dense valley. In my excitement of seeing a leopard, I didn't even realise that I had just seen my first Nilgirilangur, a Western Ghat endemic primate that I had longed of seeing in the wild for the longest possible time. Is it why large charismatic cats attract disproportional conservation attention?

When I thought that I had enough, one more leopard, a full grown male this time, crossed the road right ahead of our jeep as we approached the Nalumukku tea estate.

However, the most exciting drive of that eventful day took place at night, from Kodayar to Rajans', our food manager and man Friday during our ensuing field trips at Kodayar. Two porcupines, eight sambars browsing among the tea bushes and a nightjar roosting on the road, were all stunned and bedazzled by the headlights of the sturdy Marshall.

After the excitement of all those sightings died down, I could reflect on a couple other observations that struck me about that maiden trip. Firstly the metalled road running right upto the Kodayar field station bemused and baffled me to no end. All the PAs that I had visited in Assam and Mizoram till then had, at best, dirt road or merely animal trails running through it. So much so that it would have been impossible for me to imagine a PA without bad roads.

Secondly, during the drive to Kodayar from our base-station at Singampatti, we halted mid-way at Manjolai tea estate for a cup of tea. Munching on the cold and stale uzhundhuvadai, the glass panes of the canteen's window, the mist and the frondescence of the endless tea bushes, the silver oak and the distant immutable forests, all reminded me of Cheenu's ( played by Kamal Haasan) Ooty cottage in BaluMahendra's stellar film MoondramPirai. Subsequently, I made several trips to Kodayar via Manjolai but none could recreate the magic and excitement of that first time. Like Cheenu, perhaps my wisdom and experience too came at an expensive pricethe permanent loss of innocence and foolhardiness.

- Rajkamal Goswami

rajkamal@atree.org

The Dark Wall

After a long wait at the check post in the hot plains, we drove with provisions and camping equipment for 7-8 enthusiastic students and a youngish enthusiastic Prof. into the Ghats. The year I guess was 1989. The road wound through teak forest and then started to climb, the forests gave way to open grassland with scattered trees and the distant hills were drawing closer. It was an exhilarating drive for me and at every bend I was expecting some animal or other to be standing waiting for us to catch a glimpse of it before jumping into the bush. We skirted valleys and crossed streams before driving through dense and tall forests that was just beautiful and almost like being in Eden. We reached our destination right inside KMTR by evening. The last bit of climb was too stiff for the vehicle and so some of us jumped out and walked. I was just waiting for this to happen: to be among the hills and forest just as the dusk setting in and the dark jungle roaring to wake up. Memories from the pages of Corbett and Anderson came flooding into my mind.

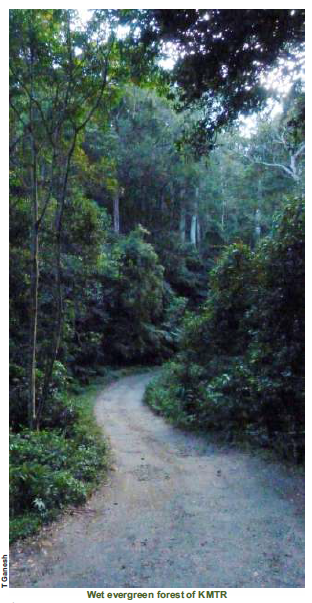

As my colleagues were busy settling themselves and chatting about, I slipped out of the cacophony and walked away from the guest house towards what looked like a path into the forest. By now it was dark and as it happened I did not have a torch. The path diverged from the main road by which we had come and there I was stuck. The path which till then was visible in the starlight suddenly seemed to disappear into a black wall. I stood at the edge of this precipitous unknown wall and did not know what to do. I could still hear the cacophony of my companions clearly enough in the stillness of the night when suddenly the urge to be in the comfort and safety o f t h e c r o w d s e e m e d overwhelming. But something deeper within told me to hang on, to see and experience the unknown. And so I stood there. The black wall suddenly seemed to dissolve as my eyes got accustomed to the darkness and I could see some blur of a path in front. I gingerly took my first step forward expecting an elephant to whip me up any moment or a bear waiting round the corner to embrace me in that final hug. With more guts I took a few more steps and soon I was amidst the blackness. My eyes now were like a nightvision scope; I could see huge tree trunks that just seemed to disappear into the star lit sky, the sky itself as I could make out was festooned with myriad shapes of leaves and branches through which I could see a few stars dance between swaying leaves. I could not fathom the height of the trees but they were tall, huge and dense. I was overwhelmed and humbled amidst these giants. The forest was not silent, there were sounds that seemed far and eerie but there were also calls of insects, frogs, water gurgling, wind rustling the leaves, all of which aroused an element of mystery and fear within me. The cool wind told me to head back, this time the steps moved faster but in the reverse, the fear of some demon lurking among the giants waiting for me to turn my back, to do the needful for intruding into their domain was just too strong. I was soon out unscathed, the black wall stood there less forbidding but with full of mysteries and I walked back to the din of my colleagues with awe of what I had experienced. As people shared their experience I sat silently in a dark corner watching the stars twinkle over the canopy of grass. My experience with the dark evergreen forests that night was just a beginning of a long and beautiful voyage. Something similar to what W.H Hudson felt as he stumbled through Amazon in search of Rima and exploring the intricacies of a rainforest ecosystem.

- T. Ganesh

tganesh@atree.org

Recollections - misty yet magical

Honestly, I cannot remember my first visit to the KMTR field station as it was then known. It seems like over the years, several visits have telescoped into a rich `3D' memory of the place! I will share a few that come to my mind. For me going to Singampatti where the field station was located in a rented building would always conjure up memories from my childhood when I would go to my grandmother's house in Nazareth and Thisaianvillai villages, not far from there in the same neck of the woods. So in some sense it was like going to my roots. The verdant green paddy fields, against the backdrop of the majestic Agasthiyar range will remain with me for life. I remember at some point, my colleagues experimenting with some innovative designs in paddy agro-forestry and that initiative included local school kids to plant more trees in the by lanes of the erstwhile capital of the local Rajah. He is entirely another story, as he seemed to leap out of the pages of an Amar Chitra Katha comic into life. A living relic, but a wonderful person. Meet him before he too passes on into the history books. Visiting his old palace and well-kept museum were highlights of one of our trips there. I still remember he looked at my fatherin- law from the US and with a twinkle in his eyes said that the old spears still had dried British blood! KMTR field station and its activities in the reserve are intricately linked with the person of the Rajah of Singampatti. I hope someone else will put pen to paper and share that colorful and unique history of this relationship. Once after a hot day's work we indulged in a cool swim in one of the canals that carried water from the Manimutharu dam to the fields. Watching the sun go down, while floating in the water, surrounded by the Agasthiyar peak was a special joy and remains etched in my mind. Making the jeep trek to the upper rainforest camp where the team had renovated an old building of the Tamil Nadu Electricity Board was quite an adventure. It seemed that the building was coming down around the old table, chair and beds, but they had the temerity to still use it. They said that they shared the quarters with a large rat snake who used the rafter as her highway. I think now it is just rubble, and the rat snake has moved to a better accommodation. Not far from it was a giant tree with a rickety ladder nailed to it reaching into the distant canopy. This was my first introduction to the dangerous, yet magical world of canopy science. I went up a few steps and decided canopies were best left to others more endowed to study it. I would just work with seedlings!

The KMTR field station was renamed the Agasthyamalai Community - based Conservation Center (ACCC) some time back and we moved to a new location, a short distance from Singampatti. Now with several acres, a dorm, nice offices and an incredible view of the Western Ghats, the next 25 years is for a new generation of ecologists to make their own and make conservation and sustainability everyone's concern. If it were not for the tireless and pioneering work of Soubadra, Ganesh and Ganesan who started with a dream when they were doing their PhD long time back, I would have no memories to share, and there would be no ACCC for a future generation of students and leaders. I am grateful to have shared a part of this history.

- Gladwin Joseph

gladwin.joseph@apu.edu.in

The many first time visits

Even before my first visit to KMTR, I had created a mental image of the forest by reading many articles on the landscape. One aspect I had read many times was that there are five species of primates, bonnet macaque, Nilgirilangur , common langur, lion tailed-macaque (LTM) and the slender loris apart from charismatic species like tigers and elephants. I was very keen to see the LTM and the loris which had eluded me till then. In 2007, I joined a project in ATREE whose primary focus and activity centered on the peripheral regions of KMTR. So, for about a month since my visit to the landscape, I had to be satisfied with a view of KMTR from the outside. Soon I got the first opportunity to visit the KMTR 'forests' when I volunteered to help with an education trip led by Soubadra and Mathivanan for school students. We took the road to Nalumukku, a tea estate inside KMTR. After refreshing ourselves at the tea shop, we started walking with the students towards the 'wooden bridge' where all the while Soubadra patiently replied to most of students queries on the new plants and animals they saw. When the students saw a Cullenia tree that Soubadra had been using for her study, they all wanted to climb the 25 m tree which thankfully had a rickety ladder attached to it. Meanwhile, Arun and I started to explore the forest ourselves. As we walked, we saw a blue tailed skink, an imperial pigeon and many other animals. After we crossed the 'tin shed', we heard a strange howl but could not trace the source of the sound because of low visibility. Even though it was mid-day, light barely penetrated through the canopy. At a distance we suddenly saw a lone lion tailed macaque and I got really excited as it was my first sighting of this threatened Western Ghats endemic. Before the disappointment of sighting merely one individual set in, the LTM which was on our left side crossed the roads via the canopy and more LTMs started appearing. The first one was perhaps a sentinel signaling to the others when the coast was clear. We noticed that each individual was behaving differently. A juvenile that we saw attempted to check every hole or depression in a tree; some LTMs would ignore us while some would be extra cautious. One such LTM drew my attention as it would keep watching us before it made even a small move. Only when it came close I realized it was carrying a young one. At this point we decided to stop following the troop. After the trip I was very happy that I got to see the LTM the first time I visited KMTR. However, to see the loris, I had to wait till 2010 to complete my sighting of all the five primates of KMTR. But a journey in KMTR is never complete. Once, I saw spiders that were comfortable under water using a bubble in their abdomen as an oxygen tank. In another instance, I saw a blue gecko with beautiful markings on its orange head. I have realized that the forests of KMTR have something new to offer every time I go and each time is like a first visit.

- Allwin Jesudasan

allwin.jesudasan@atree.org

All but the first impression were good!

The pressure to earn bread and butter after dropping out of school was imposing which drove me to help my household. My parents were engaged in the mundane job of tea picking, the money from which was not enough for our family. What were the opportunities in the BBTC tea estate embedded in KMTR for a 12 year old lad? Nothing. I used to envy seeing my 'machaan' (uncle) Ramesh, a research assistant, hop on to the researchers' jeep and head towards the forest. One day to my surprise, machaan announced that I might get a job with researchers in ATREE. I put on my best clothes and joined the team. First day in the forest was not good at all, rains lashed down heavily and we came out with our feet drenched in blood bitten by leeches. I had second thoughts of continuing and even thought of quietly slipping away for good. Thank God, it did not leave a lasting impression. Next day I was there at Nalumukku again, armed with aruval waiting for the 'researcher's jeep'. It is now almost 15 years since I started helping researchers in KMTR. I started as a research assistant first with Pondicherry University and then with ATREE.

Over a period, I slowly started tree climbing with my uncle and setting ladders for madam's (Soubadra) pollination work. I imagined myself to be an engineer involved in complex construction having arguments with machaan on how best to angle the ladder and place the platforms on the trees which were often more than 22mts tall. Thrilling experiences have always been with TG sir (Ganesh) on his night transects. I loved the laborious work of measuring trees for RG (Ganesan) but I hated doing visitation of flowers for pollinators for madam. I could never doze off under her watchful eyes! I remember when the trek to Agasthyamalai was announced, I was still small kid and therefore had to demonstrate my stamina by scaling the valve house cliff in 15 minutes which I did with ease. Although I have trekked the Agasthiyar peak 3 times, my first one was memorable because this was with the team of 5 -RG, TG sirs, madam, Ramesh machaan and me. I have walked the forest alone on many occasions and seen almost all the denizens of the forest. Strangely the first encounter with an animal close to the Palaquium stream in Green's trail, kept me wondering what this creature was, it took me years to fathom that it was a tiger.

- Tamilazhagan (as narrated to Soubadra Devy)

chiyanaccc@gmail.com

KMTR - abode of the biggie or is it one big botanical garden!

In Pondicherry, where I grew up, wilderness to me were the ashram farmlands around Ousteri lake where we watched many birds and butterflies but never bothered to identify them. Things changed in 1988, when I found myself in M.S. Ecology course at Pondicherry University and within 6 months was aboard the Nellai express to reach KMTR with my classmates and Professors Rauf Ali, Priya Davidar and Parthasarathy. Barring a few of us, most of my batch mates were seasoned trekkers and birdwatchers. We landed in Mundanthurai where I was soon bundled off with the bunch of classmates with botanical slant (rather—no exposure to wildlife) to Sengalteri, while seasoned rest settled to do the monkey business (studying primates).

We were led by none other than the plant taxonomist 'Partha' . The winding road took us to the bungalow, which overlooked the grassy hills at Sengalteri. I was in real wilderness at last, hopes rose - anticipating tigers, leopards, and elephants at every turn of trails we took- but only encountered Partha's discourse on plant taxonomy. `This is Cuuuuuuuulleniaexarillata' he would stress and I saw my botanists friends collecting its spiny fruits and seeds from the litter. Of course, with reluctance I picked one too. Day and night we were picking up plant twigs and identifying them under hurricane lanterns. We did not see any biggies (elephants and tigers) at all, our trackers would just point out to old dungs and to the so called pug marks. Black leaf monkeys (Niligirilangurs) were the only solace. The trek to Nettarikal was amazing of course, picture card of little rainforest brooks, huge towering old trees whose head we could hardly discern but never failed to catch my attention.

Now convinced that itwas safe haven, with no biggies lurking, I developed the habit of trekking to Kuliratti, a rocky outcrop with a sunny stream, in the afternoons which attracted hundreds of butterflies! Later when I worked on butterflies in Kakachi part of the park, I realized that butterflies were more active in the midst of sunlit canopies as were other pollinators whom I used to watch perched on the canopy of some of the tallest trees of KMTR. By then I got used to the 'beautiful botanical garden' and the insidious ways in which the smaller creatures interact with plants. Although I have shared the space with the biggie (tiger) for 15 years I am yet to have collusion with her or him. However, I don't miss them much as I have been already bewitched by the many other smaller but not any less interesting organisms.

- M. Soubadra Devy

soubadra@atree.org

Forest full of surprises

On the eve of my first trip to KMTR, when I excitedly asked other people about their experiences and their best recollections of it, I was told that the trees are tall and the forests dense with the mighty Agasthyamalai peak adding an immeasurable grandeur to it all. An overnight bus ride brought me to Agasthyamalai Community - based Conservation Centre located in the foothills of KMTR. The first thing I noticed about the field station was the friendly staff, the lovely architecture, and a teeming nursery. The Agasthyamalai could be seen far away amidst the jagged mountain range. It was difficult to imagine what lay between the ACCC and that peak.

The next day we started travelling towards the ATREE field station atop mountains. A thing which forever was etched into my mind was the travel itself! I looked with awe at the bus drivers which proficiently tackled each of the numerous hairpin bends on the way. But soon the bustling journey and excitement was soothed by the tranquil emerald forests. We stopped on the way to have tea, not any tea, but a fresh brew from the surrounding tea estates itself! Nobody told me about these tea estates earlier while describing KMTR and I sure was slightly taken aback. But I bet a ruby-colored concoction of steaming fresh tea would make anybody's heart lighten. Before reaching the mountain-top field station near a dam, we had seen the tall dense forest, but again not without the surprise of passing an old British golf-course on the way.

In the next few days I saw the trails the old botanists had made, and the forest which had regrown after being clear-felled. Looking at the Malabar tree nymph gliding over us, watching the black eagle soar in the valley, meeting the lion-tailed macaques, and the beautiful ferns, all of it is fresh in my mind. The countless leeches and the spiny climbers aptly named 'wait-a-while' increased my admiration towards the forest. I equally enjoyed an evening with rock eagle-owls in the drier parts of KMTR.

My first impression of KMTR was formed by a step-by-step process full of revelations. In the process, I gained newfound respect for ATREE's researchers and staff who have fought odds to understand KMTR better. After that small trip, I feel that KMTR is one of the most diverse forest patches in our country! I am sure that right now KMTR stands ready, to surprise each and every explorer.

- Ovee Thorat

ovee.thorat@atree.org

Memories of KMTR

I first visited KMTR along with Ovee Thorat, Venkat Ramanujam and Ronita Mukherjee, my fellow scholars, to take part in the practical of the plant-animal interactions elective course. I had heard a lot about KMTR from Ganesh (my PhD supervisor) and Soubadra (our course instructor) both of whom used plenty of native examples from KMTR during the ecology course. Besides I had already read several papers about the incredible biodiversity of KMTR. Therefore, before my actual visit, I already had visualised KMTR as a brilliant green forest with a towering canopy! Needless to say, I was not disappointed an ounce as I set foot on KMTR for the first time. The spectacular ride up from the ACCC field station at Manimutharu at about 100 m to the Kodayar field station at 1,300 m gave me an opportunity to see dry, moist and evergreen forests in just a span of a few hours. The verdant wet evergreen forests above Manjolai and Kodayar were a first experience for me, being used to mainly dry deciduous forests from my earlier work in the Eastern Ghats. My two weeks stay in KMTR were spent walking transects and laying plots in the forests around Kakachi, along with Soubadra and my fellow students. The almost daily sightings of endangered species such as the lion tailed macaque, Nilgirilangur and the one lone sighting of the endemic brown palm civet allowed me to appreciate the biodiversity and the importance of conserving unique forests such as KMTR. The experience left me with pleasant memories and images such as the Upper Kodayar dam, resting at Fern House after a long walk, tea at Rajan's hotel in Nalumukku and of course, the blood sucking leeches that I was left with every day! KMTR was quite simply unforgettable and magical.

- Vikram Aditya

vikram.aditya@atree.org

Wanderings through southern end of the Western Ghats

My first trip to KMTR was in 1989 shortly after commencing my BSc in Madurai. Having made the decision to pursue a research career in wildlife and conservation science, I was quite eager to explore as much of the Western Ghats complex as possible, and Mundanthurai WLS just happened to be the first of many protected areas that I would visit in this spectacular biodiversity hotspot. Those were heady days for a budding naturalist and risk-junky. I vividly recall walking off after dark, by myself into a forest that was home to tigers, leopards, sloth bears and elephants. I also was very fortunate to be guided during many nocturnal walks by a gentleman named Mani, a member of one of the local tribes with considerable knowledge of his backyard…and what a backyard it turned out to be! Some never-to-beforgotten moments were encountering an Indian spotted chevrotain or mouse deer along a stream, almost stepping on a large Indian rock python stretched across our path in the dark, having a stare-back session with an Asiatic wild dog across the Thamirabarani river, and having the living daylights scared out of me by a leopard giving its rasping call right outside my dormitory window in the dead-silence of the night.

During subsequent visits to this tiger reserve, I trekked into wetter forests draping the hill slopes. The ground during one such trek was teeming with leeches, as a result of which I ended up with sores on both feet. While strolling through a cardamom plantation that seemed to blend with the forest a loud flapping of wings caught my attention and resulted in my first ever sighting of a magnificent mountain imperial pigeon. Liontailed macaques made their way through aerial walk-ways in the tall trees shading the plantation.

It was only in my final year in Madurai that I did manage to visit the 'Kalakad' section. We traveled through the low-elevation dry deciduous forests to the moist deciduous and evergreen habitat in the higher reaches. Memorable moments were a sighting of the gigantic Indian tiger centipede, as well as chancing upon a southern green Calotes struggling to gulp down a large prayingmantis. These are some of the many memories I retain of KMTR, often with friends, trekking through the forest, raising a ruckus to alert a sloth bear that seemed oblivious of our presence, having a nightjar hawk insects hovering above our heads, and simply cooling off in a river staring up at a large stork-billed kingfisher perched on one of the riverine trees.

- Dhananjaya Katju

dkatju@gmail.com

A nymph that turned me on!

I started visiting KMTR in 2007, when I was 14 years old. The experience since then has been a journey of endless learning. Otherwise, my exposure to the environment was a small section of the biology subject in school. Initially, there were many field visits to help in identifying the birds in wetlands. Then came an announcement of a camp inside the sanctuary, up in the mountains to be organised by the ACCC. It also said that a test will be conducted to select students for the camp. The test had two components -a test on identification skills was judged by projecting pictures of various bird species which was followed by a written test. Fourteen of us including me cleared both the components and so at 5 am the next morning, we left ACCC and crossed the scrub, teak and savannah patches before reaching the evergreen forest. Our first destination was Kakachi, and we went through the famous green trail which ATREE researchers used. We saw lots and lots of plants and trees. Then we climbed the ladder on Cullenia exarillata and saw an instrument on the tree called HOBO which measured and recorded the temperature, humidity and light. We continued on the trail and saw the Nilgiri green pigeon and emerald dove better known as Maragatha pura our state bird. By then, we were bitten by many leeches but the Malabar tree nymph flying past soothed my senses and made me forget the bloodshed caused by leeches. The drive down was also memorable as we saw a gaur with her calf. I am happy that my journey continues as a volunteer with ACCC which gives me an opportunity to visit the beautiful forest and I feel lucky to have this area at my backyard. The Malabar tree nymph sighting triggered my interest in butterflies which now has become my passion. I am now co-authoring a bilingual guide on butterflies in the landscape surrounding KMTR.

- Thalavai Pandi S

enviropandi@gmail.com

Isolated Haven

When I first visited Upper Kodayar in KMTR it was October and the forest was wet and green. I was put up in an isolated accommodation surrounded by forest of lofty green trees and quiet flowing streams, a place I used to dream about when I grew up. What charmed me about Upper Kodayar was its isolation, greenness and the two dams, which I frequently visited. The trails through the forests were narrow and infested with leeches which made field work very difficult, especially counting and identifying fruit species in the ground. The best part was watching fruiting trees for visitors, which made animal observations very personal and interesting. There are many firsts for me in Upper Kodayar, it was the first time when I worked in a wet evergreen forest, the first time when I did serious ecological work, and the first time when I saw many species of birds and mammals in the wild. Exceptionally interesting moments were sightings of small mammals such as brown mongoose, brown palm civet, Nilgirimarten, the acrobatics of the Nilgirilangur and the teasing antics of the lion - tailed macaque. Overall,an unforgettable, and to-date the best field experience ever. Hope this place remains verdant, and a happy home for animals.

- Patrick David

patdavid28@gmail.com

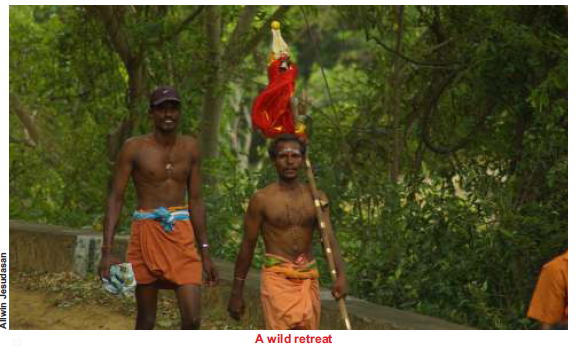

Old men by the river

My first thoughts of KMTR were formed even before I visited it, through a field guide that I was editing. The text of that book told me that habitats ranged from dry forests to the wet evergreens. As a matter of coincidence, a more glaring introduction to the place came from one of our senior colleagues who chose to make a presentation on the gory issues related to temple tourism while all of us were gearing up for a visit. The first visit was of course to the temple site (Sorimuthu Iyyanar kovil) and I remember being perplexed on what to carry or what not to carry, since the stories of animal sacrifices, open defecation, and mass movement of people to the forest had created an alarming idea of the place. In the days that followed, the crowd emanating from the long convoy of vehicles past the dormitory we were housed in, was localized to the twenty five hectares around the temple whereas its repercussions had the potential to ripple off far beyond. The lasting impression however came from a few old men, who chose to rest on the sandbanks far away from the muddling and jostling crowd - It seems that forest is highly inaccessible to the common man, even when they were seeking a benign and peaceful visit. The forests stretched into many hundreds of hectares beyond the route to the temple, but a visit remained out of bounds or was restricted to the crowded locations around streams and waterfalls. However, from the subsequent visits over the years, the impressions seem to take as many twists and turns as that of the river by which the old men were resting.

- Prashanth M.B.

prashanth.mb@atree.org

Event Report

From Mundanthurai to Ranthambore

In 2006 a highly inspired Field Director called upon us to draw a plan of management for countering the ill-effects of the Aadiamavasya temple festival in the Sorimuthu Iyyanar temple located in the core area of KMTR. First, we were perplexed at the call, but decided to respond to the commissioned project. We hired a few bins and placed it in various locations and got the garbage collected. It was indeed a token effort, but gave us the actual perspective of the festival. The pilgrim's number that made to festival kept shifting from 200000 to 500000 from various sources. It took us all a while to actually recover from the shock. So where do we source funds for this project? Can anything be done at all?

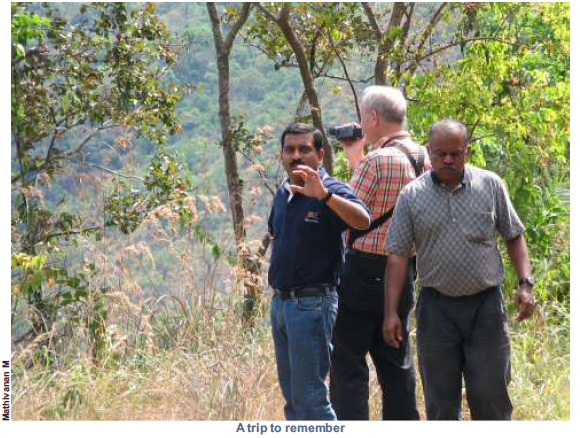

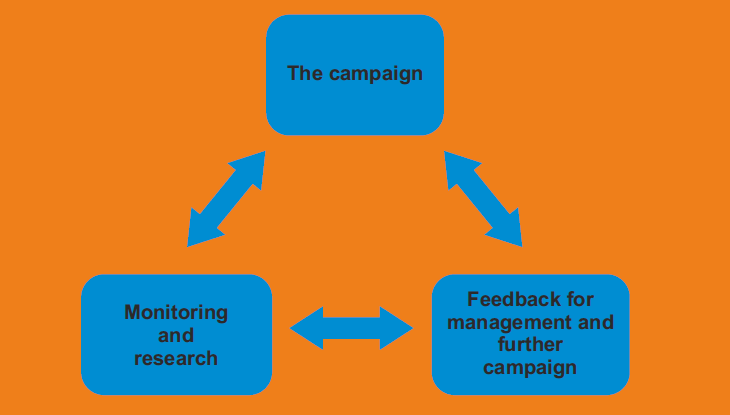

An equally inspired school kid who visited KMTR with ATREE researchers in 2007 decided to do something for our team and helped us procure a grant of Rs 70,000. We drew a plan for the campaign devising various strategies to reach out to the pilgrims. Alongside, we developed a monitoring protocol to measure the impacts of the festival on the biodiversity and the environment. We also monitored the attitudinal change of the visitors over time through a specially designed social survey while the pilgrim numbers were estimated through a vehicular survey. The data from the monitoring exercise served as a feedback for management and the campaign.

From TNFD-ATREE partnership the number of stakeholders grew _ comprising the Pancahayat bodies, Municipalities corporations, NGOs, businessmen, citizen and civil society groups and individuals. More importantly the media supported us and they began to highlight the ill effects apart from glorifying this festival. More than 300 volunteers from the landscape and team of researchers from ATREE Bangalore were at task during the festival for 5 years. Efforts were made to transfer this model and experience to the local stakeholders over the years.

We consciously stayed away for 2 years. This year, we revisited the festival responding to current Field Director's call. To our relief and satisfaction 'our model' is persisting in the memory of the system. Additional moves such as ban of digging and clearing equipment was enforced in order to restrict people from clearing vegetation. Thanks to this success story, we have been invited to implement 'the model' in Ranthambore this August where a Ganesha temple draws double the crowd. If we demonstrate the model successfully there, there is a good chance that NTCA will implement it in all the tiger reserves across the country.

- M Soubadra Devy

soubadra@atree.org

Snippets:

- A Russell's viper was seen in ACCC nursery during the plant systematics course in May. Muthaiah, Mathivanan M, Ramya R, Sutapa Mukherjee.

- Asian brown flycatcher was seen in June in ACCC. Thalavai Pandi S

- Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), a migrant wader, was spotted on July 29th near Tiruchendur beach. The migratory birds are more commonly seen between the months of September to April. - Prashanth M.B.

- An adult common krait and a brahminy worm snake were seen during the stay in the ACCC in July. Allwin Jesudasan and Prashanth M.B.

- Black rajah (Charaxes solon), a nymphalid butterfly, was seen at Nanalkulam village, Vagaikulam on 16th August, 2014. Thalavai Pandi S

News, Talks and Presentations:

- Plant animal interaction course was conducted in ACCC between 17th to 20th April 2014 by M. SoubadraDevy.

- Plant systematics course was conducted in ACCC between 13 to 25th May 2014 by R. Ganesan.

- "See U India", a course for Columbia University students, was conducted in ACCC between 17th June to 1st July 2014.

- Kieran Flood from Ireland completed his internship on heritage tree mapping in buffer villages of KMTR under the guidance of M. Soubadra Devy.

- P. Arulmozhi Varman and P. Pranavi students from Azim Premji University, Bangalore interned with ACCC under the guidance of R. Ganesan. They followed up work on the heritage tree mapping.

- Mathivanan attended the preparation meeting on Sorimuthu Iyyanar Temple's Aadi-amavasya festival held at KMTR Field Director's office, Tirunelveli on 8th July 2014

- Mathivanan and Dr.Soubadra Devy gave motivation lecture for volunteers on Sorimuthu Iyyanar Temple's Aadi-amavasya festival held at interpretation centre, KMTR, Papanasam Range on 24th July 2014

- ATREE-ACCC conducted traffic and social survey during Sorimuthu IyyanarAadi-amavasya festival (25-27 July 2014)

- K. Karthikeyan, K. Keerthi Srinivasan and R. Arunprasad from Regional Centre for Anna University, Tirunelveli are pursuing an internship with ATREE under the guidance of T.Ganesh.

- Ms. Irene Klock , an under graduate student from University of Oregon is currently pursuing her internship with ACCC on 'People perception on Thamiraparani, Nambiar and Karumeniar river interlinking project' in Tirunelveli and Thoothukudi districts of Southern Tamil Nadu under the guidance of M.Soubadra Devy.

- Ms. Anna Spiller, an under-graduate student from Noragric Dept., Norwegian University of Life sciences, As, Akerhus, Norway completed her internship in the project "Ecosystem service offered by bats roosting in temples and dilapidated building in a human dominated landscape". Her internship period was from 11thOctober to 31st December 2013.

Publication:

- Seshadri, K. S., Gururaja, K. V., & Bickford, D. P. (2014). Breeding in bamboo: a novel anuran reproductive strategy discovered in Rhacophorid frogs of the Western Ghats, India. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

- Seshadri, K. S Herpetology Notes, volume 5: 201-202 (2012). Occurrence of large-scaled pit viper Trimeresurus macrolepis Beddome, 1862 in the forest canopy of Kalakad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, southern India.